Reverse engineering Bluetooth LE LED light controllers, or How I Bricked My Christmas Lights

If a device communicates via Bluetooth LE and has an app, it deserves to be integrated into my home automation system.

I’ve spent a significant amount of time reverse engineering various budget-friendly LED light strips to automate them. The process is generally repetitive, but I find it enjoyable. Recently, I successfully connected the cheapest lights I’ve ever come across — a £2.38 Bluetooth LE-controlled 5M non-addressable strip — to Home Assistant in just a few hours. You can buy some here and the code is here.

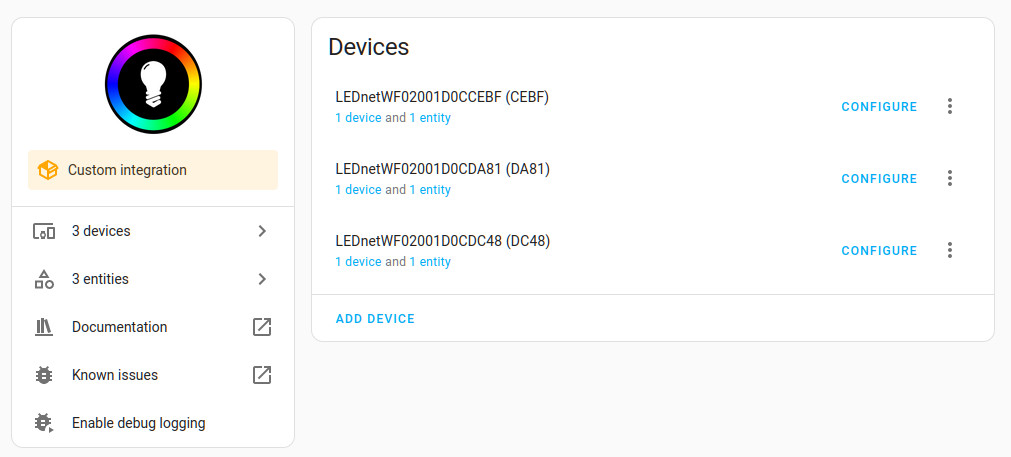

There is also the LEDnetWF controller I did the reverse engineering for here.

I also had another set of addressable lights on my desk. While decorating my office for Christmas, I decided to invest some time in connecting them to Home Assistant using the BJ_LED code as a template. It should have been straightforward, right? Well, yes, but also no.

These lights consist of a 10M long string of addressable LEDs controlled by the “iDeal LED” app. The app is feature-rich and works reasonably well. The LEDs are likely WS2812 or similar. I was quite pleased with these lights, which you can find on AliExpress.

Now, let me share a cautionary tale. While I’m omitting some details for brevity, there are no secrets here, and additional instructions are readily available online. I understand this might feel a bit like drawing the rest of the owl but the provided links should serve as a starting point for anyone interested in reverse engineering their own LED lights.

Step 1. The bytes over the wire

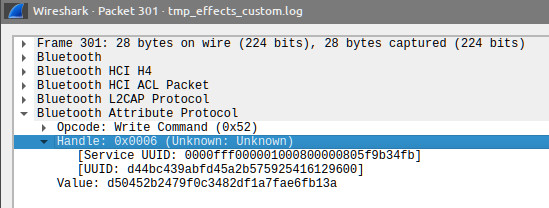

To control devices from your own software, the first step is to examine the bytes sent over Bluetooth to the device from the app. Typically, lights use a simple protocol with a header, command bytes (for actions like turning on/off, changing color), and a footer, which might be a checksum.

Android makes this process easy. Enable developer mode on your Android device, install the app for your lights, and enable Bluetooth HCI snoop in the developer settings. This logs Bluetooth bytes to a file readable by Wireshark. Perform actions in the app, such as turning the lights on and off, and use adb to copy the logs to your computer.

For example:

adb pull sdcard/btsnoop_hci.log .

Open the log in Wireshark to see the exact bytes sent to the device. Look for patterns in the values, and you’ll likely identify a series of bytes for each action, with one byte alternating between two values (e.g. 1 and 0 for on and off). Here’s a useful Wireshark filter:

bluetooth.dst == ff:ff:ff:ff:ff:ff && btatt.opcode.method==0x12

Change MAC address to be the MAC of your lights. btatt.opcode.method==0x12 is a write from the Android device to the lights.

Congratulations, you are now a reverse engineer!

Pro-tip: You can speed things up a bit by using tshark instead of Wireshark. What you really care about is the values being written to the LED controller. tshark -r <filename> -T fields -e btatt.value will dump the payload to the terminal for easy interrogation.

Sometimes your bytes will look like this:

69 96 02 01 01

69 96 02 01 00

69 96 02 01 01

69 96 02 01 00

69 96 02 01 01

69 96 02 01 00

69 96 02 01 01

69 96 02 01 00

On, off, on, off, on, off, on, off.

Sometimes your bytes will look like this:

84 dd 50 42 37 41 50 89 7a c8 2f 39 11 09 68 a8

79 d1 db a4 09 19 c2 46 a8 58 0a e7 d1 1b 78 84

84 dd 50 42 37 41 50 89 7a c8 2f 39 11 09 68 a8

79 d1 db a4 09 19 c2 46 a8 58 0a e7 d1 1b 78 84

84 dd 50 42 37 41 50 89 7a c8 2f 39 11 09 68 a8

79 d1 db a4 09 19 c2 46 a8 58 0a e7 d1 1b 78 84

84 dd 50 42 37 41 50 89 7a c8 2f 39 11 09 68 a8

There is still a repeating pattern here. There are two distinct sets of bytes, one for on & one for off, but… what? Why is it so noisy? Who designs their protocol like this? The answer is: someone who is trying to hide something.

Step 2. Replay attacks

If your goal is simply turning the lights on and off, the repeating series of bytes you observed might be sufficient for power control. Test this with gatttool, which lets you connect to a BLE device and send bytes. You’ll need to know the handle to send bytes to, which you can find using Wireshark.

For more control, understanding all those bytes is essential. Let’s go to the source…

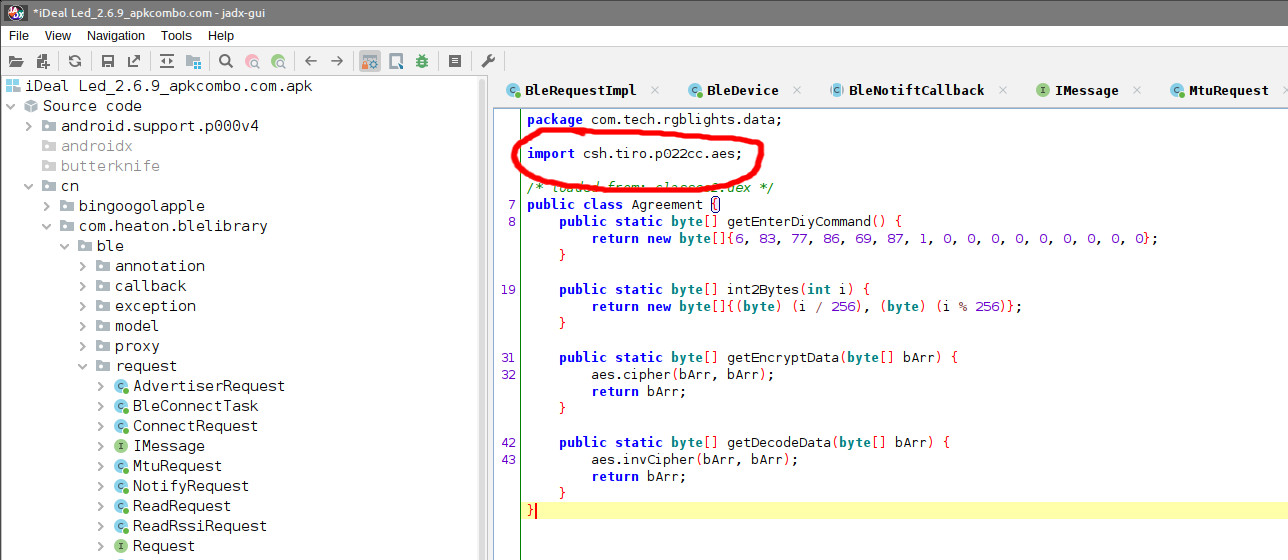

Step 3. Decompile the Android app

Download the app’s APK and open it in jadx. Witness the secrets within!

In my case, I noticed references to AES in the source, indicating a potentially encrypted protocol. If the data is encrypted, some assumptions can be made:

- The encrypted data doesn’t change every time, suggesting a consistent key.

- The data needs quick decryption on a low-power MCU, favouring shorter keys.

- The key is likely not unique to each device, making a fixed key plausible.

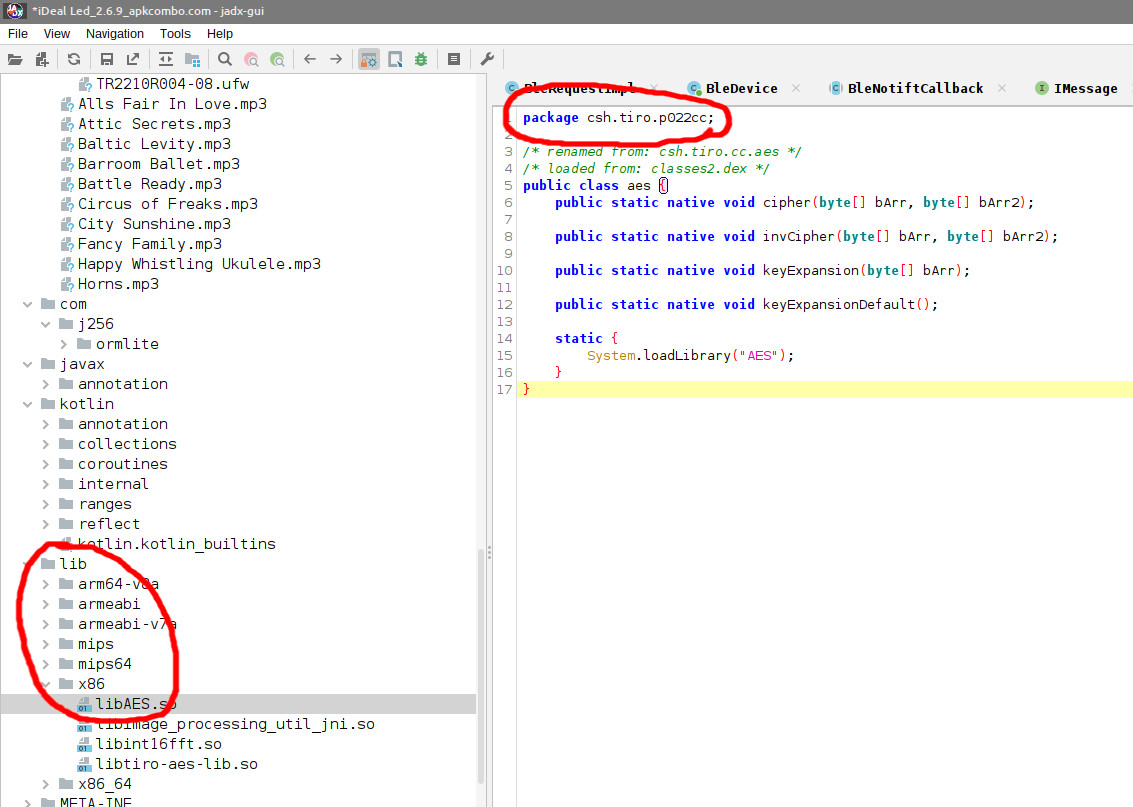

The source code contained a compiled AES library libAES.so, which jadx can’t help me with.

This is where I got stuck. For about 5 minutes.

I asked @popey and @sil for some ideas. @sil Googled some of the decompiled app code and found this page. On closer examination the code looks identical. This chap used ida free to decompile the AES library and found the key embedded in it. Let’s try that key.

from Crypto.Cipher import AES

key = [

0x34, 0x52, 0x2A, 0x5B, 0x7A, 0x6E, 0x49, 0x2C,

0x08, 0x09, 0x0A, 0x9D, 0x8D, 0x2A, 0x23, 0xF8

]

def decrypt_aes_ecb(ciphertext, key):

cipher = AES.new(key, AES.MODE_ECB)

plaintext = cipher.decrypt(ciphertext)

return plaintext

When we try and decrypt the on and off packets we get:

05 54 55 52 4E 01 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00

05 54 55 52 4E 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00

05 54 55 52 4E 01 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00

05 54 55 52 4E 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00

05 54 55 52 4E 01 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00

05 54 55 52 4E 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00

Success! This is a lot more sensible. A fixed header, byte 5 switching between a 1 and a 0 for on and off, and a bunch of zeros.

We can now decrypt all the packets being sent to the device and we can encrypt our own bytes so that we can duplicate the controls from the Android app in our own code. It’s pretty much mission accomplished at this point.

Step 4. All the functions

Now, work through each app function, recording the bytes sent. Write down each action, do it multiple times, and use separators like turning the lights on and off. This helps spot patterns and correlate notes with captured bytes.

For example, your process might be:

turn off, turn on - [start of function]

set to red

set to green

set to blue

set to red

set to green

set to blue

set to red

set to green

set to blue

turn off, turn on - [end of colour changing]

set brightness to 100%

set brightness to 50%

set brightness to 10%

set brightness to 50%

set brightness to 100%

turn off, turn on - [end of brightness]

This will help you to spot patterns in the data and see which bytes change depending on what you are doing.

Step 5. Automated e-waste generator

While exploring color changes, I observed that the app never sent a value higher than 0x1F (5 bits) for red, green, or blue. Curious, I tried sending 8-bit values, and it worked remarkably well — brighter colors!

Great success!

Excited by my discovery I got to wondering what other secrets this light controller was hiding from me. I wonder if there are any additional effects beyond the 10 that the app uses? A good way to try this out would be a simple loop.

for n in range(20):

print(f"Setting effect {n}")

set_effect(n)

time.sleep(20)

I ran this and watched 1 to 10. So far so good, then it ticked over to 11 and AH HA! I have found a secret mode! Then it ticked over to 12 and… darkness.

Oh well, I guess there are only 11 effects, that’s fine. I’ll reboot it and finish off the rest of the code.

And that was then end of my fun.

The lights never came back.

They don’t advertise on Bluetooth any more and I can’t connect to them. I’ve tried holding down the button when turning them on. I’ve left them unplugged over night to see if that helps, but no.

They are dead.

I guess I overflowed some buffer and I’ve corrupted the firmware.

All is not lost however. The LEDs themselves are standard addressable LEDs so I can at least hook the string up to a different microcontroller and use them.

Tell me how I can break my own lights

Despite the setback, I documented most of the protocol and created a Github project with a Home Assistant custom component. It works, but proceed at your own risk.